What makes a great observation night? You get to see a lot of things that you don’t get to see every day.

This night (morning of May 31, 2011) was good weather and good sight. Basically I put out the binoculars because I went to see Neptune and asteroid 4 Vesta again, which I already observed yesterday.

Neptune isn’t spectacular, it looks just like an arbitrary star and if you didn’t know its exact position, you would never recognize that it is Neptune. I use primarily Stellarium which has always been reliable and serves the purpose of letting me know where to find a particular object very well. So it also left no doubt that what I was looking at was indeed Neptune.

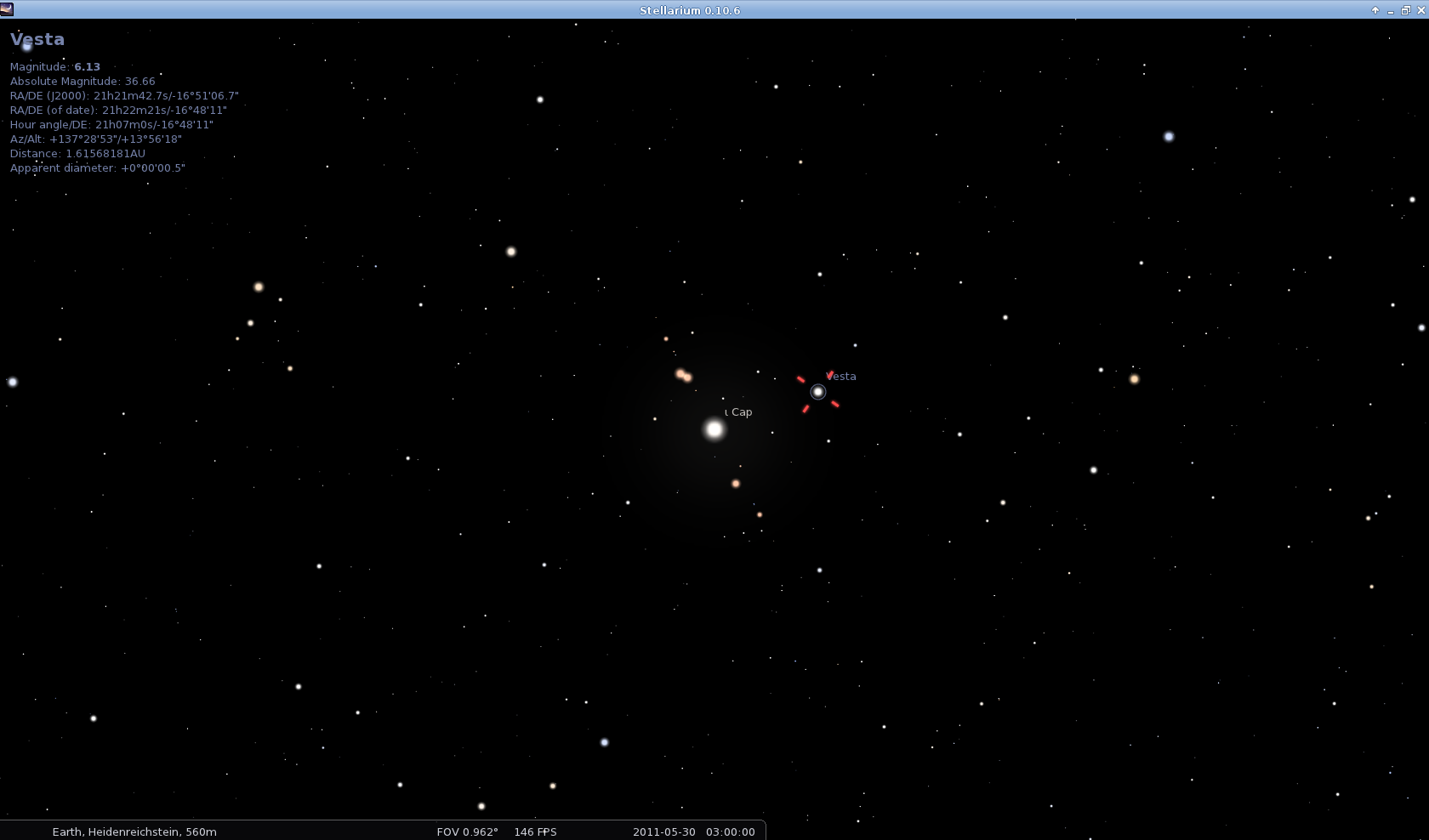

The same was true for Vesta yesterday. I knew its position based on Stellarium, and it was particularly easy because it was located very near to star ι Cap. (Iota Capricorni), which is easy to find. And since it was where I assumed it to be, there was no reasonable doubt left that I was looking at anything different.

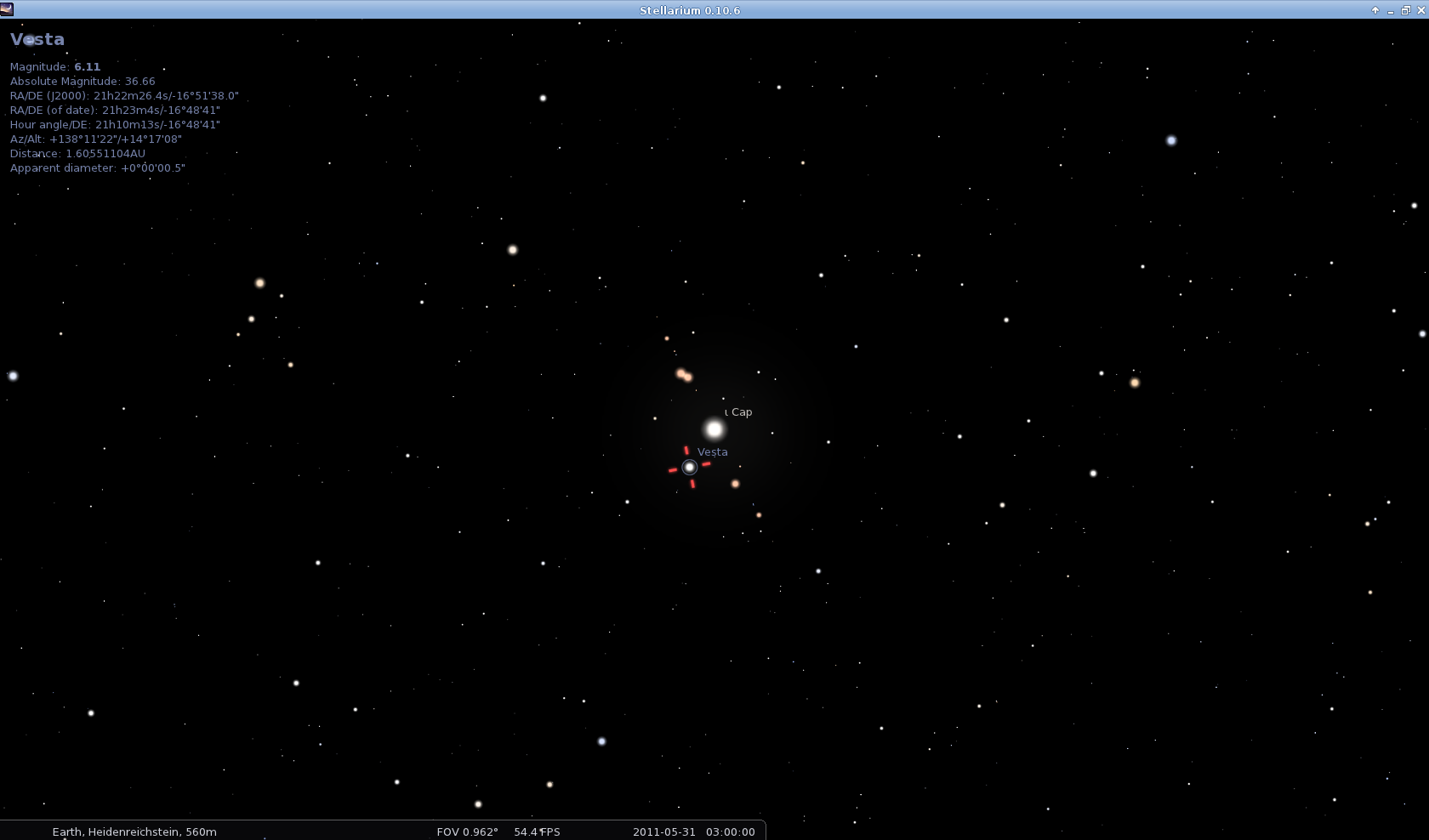

But the great thing especially about observing an asteroid is when you have a chance to look for it on 2 consecutive days, especially if it is that near to a significant star. One can see how it changed its location and that’s real evidence that it is not just an arbitrary star (even though it looks just like one).

Here is Vesta’s position of yesterday at 3am local time:

And here is Vesta’s position today:

That’s just what I’ve seen. Take this lesson: while what you are seeing may seem boring, to know what you are looking at can be very fascinating. Even though a dot in the sky may look just like the thousands other dots, it can be something very different … and to find and identify (and eventually track) them is a rewarding thing to do (in my opinion).

But there was more this night. It’s always a good idea to take a look at heavens-above.com to watch out for special observation opportunities. And this night delivered HUGE opportunities.

First thing was a Magnitude -8 Iridium Flare at 3.17am. Iridium Flares are pretty common and there is one (or more) to see almost every night. But such with mag. -8 – which is almost as bright as an Iridium Flare can get (about 17 times brighter than Venus at its brightest) – don’t show up that frequently, maybe once in a week or two. And more often than not, either the weather isn’t good or you just forget to check them out. So if there actually is such a bright one during a night that you do observing (and don’t forget to look them up at Heavens Above), you are quite lucky. And this was quite a mighty one, one of the best I’ve seen.

But the real jewels were yet to come.

The STS-134 mission is nearing its end and the space shuttle Endeavour undocked from the ISS just yesterday. This is even more significant as the space shuttle program is coming to an end, and it’s likely the last opportunity ever to see what I had the chance to see tonight (saying this with a tear in one eye, but also with a little smile as it’s time for new challenges beyond low Earth orbit).

Heavens Above showed me that the ISS was about to pass at ~3.34am this night (only 17 minutes after the Iridium Flare). When a space shuttle is on its way back to Earth, you can assume it to show up just a few seconds ahead of the ISS. There was something else that Heavens Above showed me which was very interesting. The path of the ISS led just below the very bright and significant star Deneb Algedi (δ Cap. or Delta Capricorni):

Deneb Algedi is the star in the center of the chart, right next to the 03:34:30 marker (which is the time the ISS passed it)

So I knew exactly where to look and where to point my binoculars too, which I could prepare even before the Endeavour/ISS pair showed up. I only had to wait until I could see them with the naked eye (very easy since they are both very bright), go to my binoculars, wait until they show up below Deneb Algedi, and follow their ways. An easy job even for a moderately equipped and modestly experienced amateur astronomer like me, but very rewarding.

But the really big deal about this all is that you a) neither need a big budget and b) nor need many years of experience to do just what I am doing. My Omegon Nightstar 25×100 binoculars cost € 299.00. Other than that you need only a PC and an internet connection, which you are likely to have already, if you are reading this. And last but not least, a little bit of passion for what’s going on above us.